“Western Marxism,” Yesterday and Today

In recent years, the writings of the late Italian Marxist-Leninist Domenico Losurdo have exerted increasing influence over sections of the Anglophone left. So far ten of his books and more than a dozen articles he wrote have been translated into English, along with a number of interviews. During his lifetime he was praised as an “almost unbelievably well-read” historian of ideas,[1] celebrated as “one of the great contemporary authorities on Hegel.”[2] Posthumously, Losurdo was eulogized as a boundlessly erudite militant and scholar.[3] Today he is held up by the organizers of the Critical Theory Workshop and the owners of the Red Sails website as one of their leading lights. A couple of his texts have been the subject of intense controversy, however. When Stalin: History and Critique of a Black Legend first appeared in Italian in 2008, it generated a storm of outrage. Losurdo’s final written work, Western Marxism: How it was Born, How it Died, and How it can be Reborn, has similarly stirred scandal among commentators. Even before the English edition appeared in September 2024 under the auspices of Monthly Review Press, this polemic garnered a highly critical review in the pages of a major leftwing journal.[4]

Many of Losurdo’s most outspoken promoters in the English-speaking world have suggested that there is a conspiracy to suppress the translation of his more controversial works. Whether or not this is the case is difficult to ascertain. They are right to point out, in any case, that it is mistaken to treat his books on Stalin or on Western Marxism as if they were somehow aberrant within his broader corpus. No doubt writers produce works of uneven quality; some texts will always be more worthwhile than others. But the comparative approach he adopted with respect to these topics is identical to the one he employed in his inquiries into liberalism, class struggle, nonviolence, Bonapartism vs. democracy, and revisionist history, as well as his studies of philosophers like Hegel, Nietzsche, and Heidegger. Losurdo even recycled a number of arguments he made in these works for his reconsideration of Stalin and diatribe against Marxists in the West. It is therefore futile to distinguish (as certain publishers have tried to do) between works supposedly based on real and serious research, versus those that possess no intellectual merit. Why would these books be any different from the other titles they have printed, especially given that he applied the same method to each object of study?

Yet the converse possibility also holds. Maybe this vaunted method was never all that sound to begin with. Looking at the works of his that have been rendered into English to date, in fact, it would seem that Losurdo’s modus operandi was to mislead readers with invidious comparisons while dazzling them with empty erudition. His intellectual output constitutes nothing less than the (re)entry of Stalinism into the realm of philosophy, a new school of falsification, all in service of justifying the course history has taken. Everything he wrote had to align with the geopolitical interests of those few nominally socialist states that still exist, above all China. Anything out of step with the current policies pursued by such states, or anything that cast doubt on their claim to represent an unbroken revolutionary Marxist tradition, was dismissed by Losurdo as unrealistic. This applied retroactively, as well. Marxists outside of the Soviet Union or China, who were critical of these countries’ brand of state socialism from the twenties onward, were for Losurdo seemingly oblivious to the difficulties of surviving in an imperialist world. But it extended back further still, to those Bolsheviks who rejected the Stalinist line of national industrialization. It even included Marx and Engels themselves, who in his view retained a utopian streak.

The following essay will take Losurdo’s book on Western Marxism as its point of departure, but will refer to many of his other works along the way. For ease of readability, it will be divided into three parts. Part one will interrogate how “Western Marxism” was historically articulated, especially how it was taken up by journals influential on the New Left. It will be seen that the notion was evaluated differently depending on how these journals oriented themselves toward “actually-existing socialism,” toward the question of defeat, and toward the prospect of revolutionary politics in the present. Here the methodology utilized by Losurdo will also be examined. Next, a second part will make reference to the various Marxists he disparaged, to see whether his characterization of them withstands scrutiny. Some of his careless, and at times even unscrupulous, scholarship will be demonstrated in this section. Finally, a third part will challenge Losurdo’s antirevisionist credentials.[5] Revisionism is a topic he wrote about at length, mostly when it came to the history of war and revolution, but Losurdo himself revised the teachings of Marx, Engels, and Lenin in two major respects: first by denying the need for coordinated international proletarian revolution, and then by denying that the state would ultimately dissolve in a classless society.

The career of a category

According to Russell Jacoby, the phrase “Western Marxism” first emerged during the 1920s. Westlichen and europäischen Marxismus were used more or less interchangeably to designate non-Soviet Marxism. Generally speaking, both were terms of abuse.[6] Though an opponent of the young Bolshevik regime, the Menshevik émigré Aleksandr Shifrin—a follower of Georgi Plekhanov—contrasted Western Marxism unfavorably with its Russian counterpart in a 1927 article published in Rudolf Hilferding’s Die Gesellschaft.[7] Even those who would later be identified with the tradition were dismissive of the concept around this time. Karl Korsch, along with Georg Lukács often cited as one of the foundational Western Marxists, expressed his skepticism toward “the various currents of so-called Western Marxism” in a 1938 piece for the councilist periodical Living Marxism.[8] Eight years earlier, abandoning the standpoint he had adopted in his 1923 essay “Marxism and Philosophy,” Korsch sneered at Western Marxism’s “fashionable” counterposition of Marx’s methodology with the results arrived at through its application.[9]

The first time the phrase was given a positive valence was in a famous piece by the French phenomenologist Maurice Merleau-Ponty, whose 1955 Adventures of the Dialectic mapped the diremption of subject and object, present and future, and value and fact from the end of nineteenth century to the middle of the twentieth. For him, marxisme occidental referred above all to Lukács’ heroic effort to overcome these oppositions in his 1923 collection History and Class Consciousness.[10] Writing in the aftermath of the October Revolution, he had thereby salvaged the dialectical core of Marxism from the wreckage of the Second International, where it lay buried beneath decades of reification. Merleau-Ponty took this to be emblematic of the work of the Western Marxists, a small group of communists active in the early twenties. But their heterodox Hegelianism was not appreciated. Grigory Zinoviev, chairman of the Comintern, denounced Korsch and Lukács as mere “professors” from the podium of its fifth congress in June 1924.[11] Together with Alabert Fogarasi and József Révai, they were rebuked again a month later in an article for the party newspaper Pravda, which upheld a crude reflection theory of knowledge. In Merleau-Ponty’s view, Western Marxism was a promising path not taken.[12]

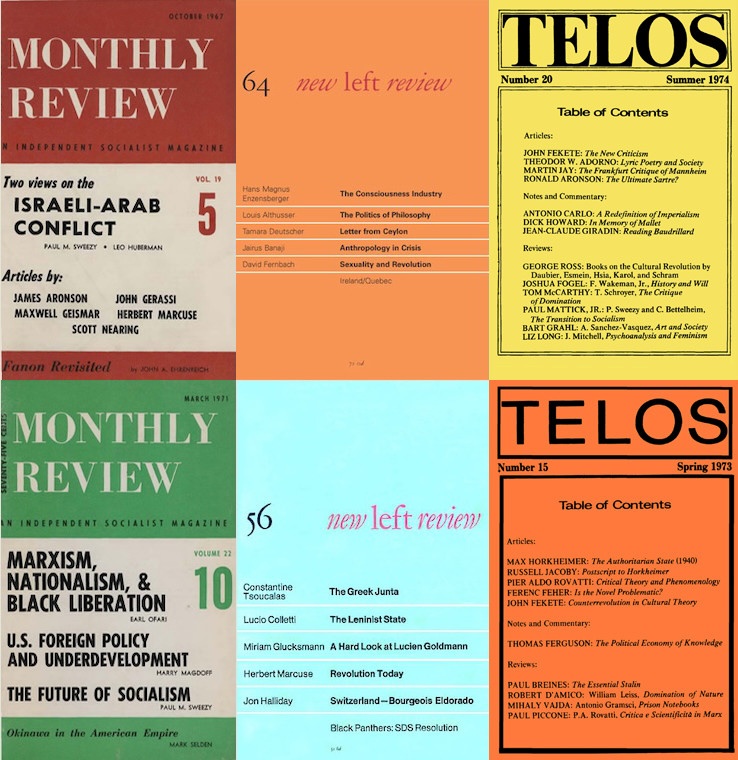

Adventures of the Dialectic came out a year prior to Khrushchev’s “secret speech,” where he revealed the crimes of Stalin. Because of the extended criticism Merleau-Ponty leveled at his erstwhile colleague Jean-Paul Sartre,[13] who had begun to align with the PCF, the book immediately triggered a backlash from party-affiliated intellectuals. Lukács even intervened to repudiate his earlier work.[14] 1956 changed everything, however. Communist parties throughout the world were thrown into crisis, first by the revelations of the Twentieth Party Congress and then by the Soviet invasion of Hungary. This marked the birth of the New Left, in the English-speaking world as elsewhere. Journals like New Left Review, Telos, and Radical Philosophy joined older mainstays like Science & Society and Monthly Review. Over the next two decades, these newer publications would elaborate their own theories while at the same time searching for dissident strains of Marxism from Germany, Hungary, France, Italy, Czechoslovakia, and Yugoslavia. Exploring the unknown dimension of European Marxist literature after Lenin,[15] writers began to speak generically of “Western Marxism.” In the sense it has possessed ever since, Western Marxism would thus seem a conceptual artifact of the New Left.

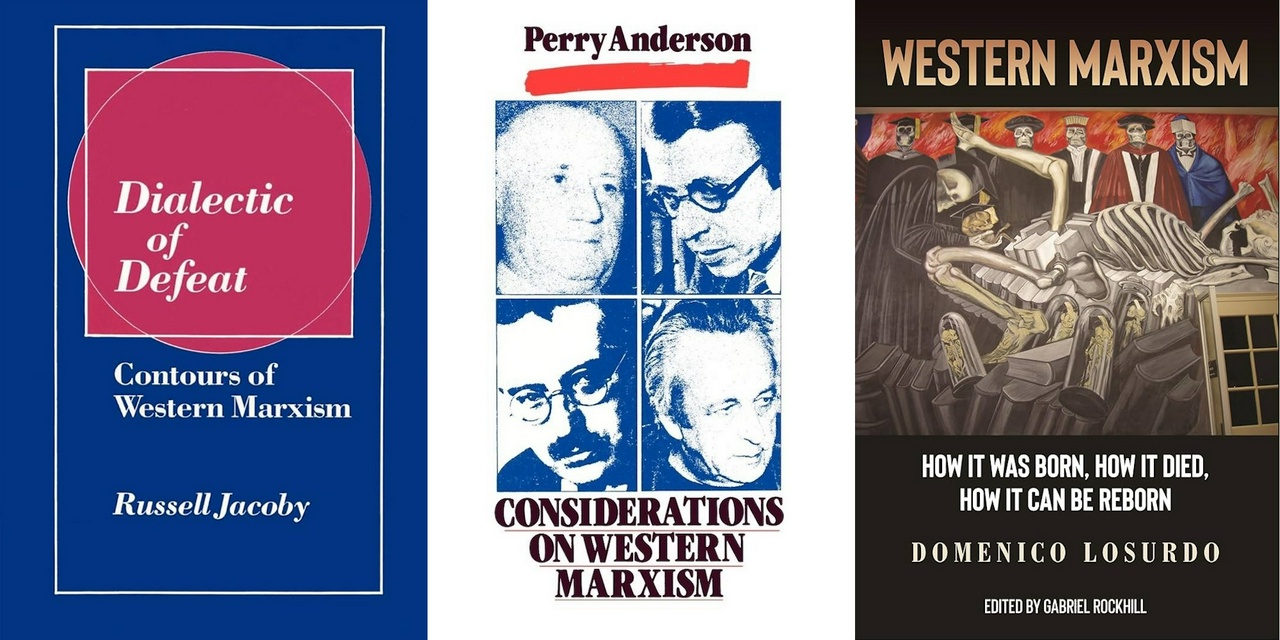

Who counted as a Western Marxist? As the phrase came to be used, Western Marxism proved a largely incoherent category, a kind of catchall encompassing wildly divergent tendencies. Perry Anderson, doyen of the New Left Review, was the first to attempt a systematic account. In his seminal Considerations on Western Marxism (1976), he included a range of figures beyond Korsch and Lukács: critical theorists like Theodor Adorno, Herbert Marcuse, and Max Horkheimer, existentialists like the aforementioned Sartre, structuralists like Louis Althusser, as well as more idiosyncratic anti-Hegelians like Galvano della Volpe and his protégé Lucio Colletti (who might be described as “Galilean” and “Kantian,” respectively). For Anderson, the thing that united all these disparate thinkers was their flight from politics and economics into philosophy, inverting Marx’s own path.[16] Anderson’s evaluation of Western Marxism was ambivalent; while he praised its theoretical ingenuity, he felt that its divorce from a revolutionary workers’ movement was a practical handicap. He saw this as a symptom of the decoupling of theory and practice in general, but thought that it left its mark in the contorted language of the Western Marxists.[17] Trotskyism at the time seemed to hold out more hope for Anderson.[18]

Jacoby’s Dialectic of Defeat: Contours of Western Marxism came out four years after Anderson’s book, providing another perspective on the matter. In many ways, it remains the best of the genre. Unlike Anderson, Jacoby defined Western Marxism rather narrowly. To him, the phrase referred exclusively to Hegelian Marxists. (Althusser, an early favorite of New Left Review, along with the Althusserian economist Charles Bettelheim, connected to Monthly Review, were branded “conformist” Marxists by Jacoby.)[19] Besides Korsch, Lukács, Adorno, Marcuse, Sartre, and Merleau-Ponty, Dialectic of Defeat also listed Henri Lefebvre, Cornelius Castoriadis, and Claude Lefort as representatives of Western Marxism, though it did not treat them at length.[20] Of course, some versions of Soviet Marxism—especially the school surrounding Lukács’ great critic, Abram Deborin—also drew inspiration from Hegel. Whereas the Deborinites looked to the Science of Logic for their system, however, the common thread uniting the Western Marxists was an emphasis on history, consciousness, and subjectivity. Hegel’s Phenomenology of Spirit was their bible.[21] Leftist currents like Luxemburgism, the KAPD, and council communism formed a political correlate to Western Marxism, which Jacoby judged positively.[22]

Losurdo’s Western Marxism is likewise framed as a response to Anderson’s Considerations, despite the forty year remove.[23] If Anderson perhaps gave an overly broad definition of the phrase, it at least had the virtue of including only avowed Marxists. By contrast, Western Marxism for Losurdo was so capacious as to include anti-Marxists and non-Marxists like Hannah Arendt, Michel Foucault, and Giorgio Agamben. Other Marxists of various stripes were added to the mix, to be sure: Mario Tronti and Antonio Negri, for example, but more recent luminaries like Slavoj Žižek and Alain Badiou as well. Most of the figures Anderson discussed in his classic text were also covered by Losurdo. The unifying principle tying the Western Marxists together for the latter was an inattention to anticolonial struggles, or disregard for the challenges they were forced to contend with.[24] Rather than face up to the hard realities of state power, Marxists in the West instead clung to vague messianic expectations.[25] As might be gathered from these claims, Losurdo’s appraisal of Western Marxism was overwhelmingly negative. He instead recommended verbally supporting developmentalist regimes in the Third World building socialism in isolation. In other words, Losurdo advocated a form of neo-Stalinism.

It is useful to triangulate the category of Western Marxism by seeing how it was interpreted by Anderson, Jacoby, and Losurdo, as sketched above. The scope of the concept, its basic consistency, and the judgment passed upon it shifted in each case, depending in part on the political outlook of the author. These books not only expressed the views of the three individuals who wrote them, though; they were expressions of three of the leftwing journals already mentioned. Anderson was, and still is, chief editor of New Left Review. Jacoby at the time was an editor of Telos. Obviously, Losurdo did not belong to the editorial board of any of these English-language publications. Nevertheless, one way to understand Monthly Review’s decision to publish his book is to situate it within a longstanding rivalry between left publishing houses. It can be seen as a belated broadside against Verso, formerly New Left Books, the imprint of New Left Review. Each of these publications cultivated an orientation toward revolutionary politics that has changed over time, and their attitudes toward Western Marxism reflect this fact.

On the politics of left publishing

In the sixties, while New Left Review’s editorial board flirted politically with Third Worldism, Wilsonism, Guevarism, and Maoism,[26] the journal translated articles by a number of continental Marxists: Lukács, Gramsci, Benjamin, Bloch, Adorno, Sartre, della Volpe, Althusser, and Colletti. Gramsci and Althusser in particular became major touchstones for the editors toward the end of the decade, only to be replaced by Colletti around the middle of the next. Anderson wrote his Considerations as “a concluding balance-sheet” to this period of activity, hoping to settle accounts with the Western Marxists.[27] The book signaled the beginning of the journal’s Trotskysant phase of the seventies, when it was looking to thinkers like Ernest Mandel, Sebastiano Timpanaro, and Livio Maitan for guidance.[28] For Anderson, Trotskyism alone had resisted the distortions imposed on other varieties of non-Soviet Marxism by the encirclement of the USSR: “The hidden hallmark of Western Marxism as a whole is thus that it is a product of defeat. The failure of the socialist revolution to spread outside Russia, cause and consequence of its corruption inside Russia, is the common background to the entire theoretical tradition of this time.”[29] Western Marxism provided valuable lessons, but New Left Review was moving on.[30]

Telos got its start in 1968, eight years after the New Left Review, but featured English translations of many of the same European Marxists as its transatlantic cousin. By contrast with the latter, however, Telos was never so enamored of Gramscianism or Althusserianism as it was of phenomenological Marxism or critical theory. Later it would drift in a post-Marxist direction, splitting into a Habermasian wing stressing the importance of civil society (the group associated with this tendency went on to form another journal called Constellations) and a Schmittian wing oriented toward populism, but during its first dozen or so years Telos championed the legacy of the Frankfurt School.[31] This explains the antipathy of its editor-in-chief, Paul Piccone, toward Anderson’s Considerations.[32] Martin Jay tried to intervene,[33] but to no avail.[34] Piccone charged Anderson and New Left Review with a “theoretical regression to Trotskyism,” itself an historic footnote to Leninist authoritarianism. Jacoby’s Dialectic of Defeat, the crowning achievement of Telos’ first phase, reconsidered the question of defeat raised by Anderson. “Do the defeats of unorthodox Marxism harbor openings for the future? Do the successes of orthodox Marxism merely mask its dismal record in the advanced capitalist countries?” asked Jacoby.[35]

Monthly Review’s stance on Western Marxism, like its stance toward defeat, is a bit less straightforward than that of Telos or New Left Review. Paul A. Baran, one of the premier theorists at Monthly Review from its first issue in 1949 up until his premature death in 1964, had a direct biographical link to the Frankfurt School. After studying for four years under the prominent Left Opposition leader and economist Evgeny Preobrazhensky in Moscow, Baran took a job in 1930 as an assistant to Friedrich Pollock at the Institute for Social Research.[36] There he met Marcuse, who became a close lifelong friend. Baran did not care for the political views of Adorno or Horkheimer, as he confided in a letter to Marcuse,[37] but appreciated their cultural criticism.[38] One of Monthly Review’s founding editors, Paul M. Sweezy, leaned on Lukács’ youthful essays on Marxist methodology and reification as well as Korsch’s 1938 Marx biography.[39] When Baran and Sweezy were collaborating on Monopoly Capital, the former insisted upon the distinction Lukács had made between method and results.[40] Despite getting cut from the final draft of the book, following Baran’s demise, an unpublished chapter quoted Adorno on television.[41]

Beyond this connection to the Frankfurt School, Monthly Review Press in the seventies published writings by authors Anderson classified as Western Marxists. Korsch’s Marxism and Philosophy, Althusser’s Lenin and Philosophy, and Colletti’s Rousseau to Lenin all came out around this time. Unlike Telos or New Left Review, however, none of the editors of Monthly Review released a book trying to summarize the development of Western Marxism. Anderson’s and Jacoby’s books were both critically reviewed in the pages of the journal, the latter faring better than the former.[42] It has only been more recently that the editorial board has weighed in on this body of thought. John Bellamy Foster, Sweezy’s successor, has thus spoken out against its “fourfold retreat”: “(1) the retreat from class; (2) the retreat from the critique of imperialism; (3) the retreat from nature/materialism/science; and (4) the retreat from reason.”[43] More broadly, Foster alleges, “[t]he problem with the Western Marxist tradition, in the sense in which Anderson addressed it and in the way that Losurdo criticized it, is that it represented a dialectic of defeat, even during those decades when revolution was expanding throughout the globe.”[44]

This oblique reference to the title of Jacoby’s book, in a sentence explicitly invoking Anderson’s and Losurdo’s treatments of the topic, once again revisits the theme of defeat. Gabriel Rockhill and Jennifer Ponce de León highlight this in their cowritten introduction to the Losurdo text. “The supposed defeat that is the hallmark of Western Marxism, according to Anderson, actually only applies to Europe, and more precisely, to Western Europe,” they maintain. “From the point of view of the global working class, this period [1920-1970] was one of major advances and some remarkable victories.”[45] Compared to Telos and New Left Review, Monthly Review has always been more supportive of “actually-existing socialism.” Baran may have despised the “repulsive oriental tyranny” of Stalin,[46] who murdered the Left Oppositionists he had known at university and prevented him from seeing his mother,[47] but he still defended the Soviet Union from Marcuse’s criticisms.[48] In spite of this fact, Monthly Review ended up taking the Chinese side in the Sino-Soviet split.[49] Once China began pro-market reforms under Deng, some of the editors vacillated. Sweezy was skeptical of these measures,[50] but lately the winds have shifted. Foster and the other editors have chronicled the magazine’s zigzags over time.[51]

Publishing Losurdo, whose Dengist sympathies are well documented,[52] would seem to consolidate this reorientation toward China. At the same time, it allows Monthly Review to snipe at Western Marxists in New Left Review’s stable of authors, by using the Italian historian as a proxy. Verso still sometimes rereleases classic titles by Korsch, Lukács, Adorno, and Althusser from its back catalogue, all of whom Losurdo targets in Western Marxism. On top of these figures, the book polemicizes against Žižek, Badiou, and David Harvey, three of Verso’s main moneymakers from the aughts and 2010s. Foster to this day harbors a grudge toward New Left Review for running Robert Brenner’s attack on “neo-Smithian Marxism” in 1978, which took aim at dependency theorists associated with Monthly Review.[53] Anderson had also made a passing swipe at Sweezy in his Considerations, claiming in a footnote that he had renounced key concepts of Marx’s economic critique such as surplus-value and the organic composition of capital in favor of Keynesian categories.[54] (This point was also made by Paul Mattick, as well as Mandel.)[55]

A brief word on Rockhill, before finally delving into Losurdo’s Western Marxism. Whatever this work’s shortcomings, which are legion, it is important to distinguish Losurdo from his self-appointed exponent, who just uses his work as a prop. Rockhill’s overriding concern is with what he calls “the theory industry”—modified from Adorno’s Kulturindustrie—rather than a thematic investigation of Marxism in the West à la Losurdo. For Rockhill, who is currently planning a trilogy on the topic for Monthly Review Press, everything reduces to a tawdry tale of US government agencies and Cold War intrigue. He makes much of the open secret that Marcuse, along with other Frankfurt School associates like Franz Neumann and Otto Kirchheimer, during World War II served the Office of Strategic Services (OSS),[56] precursor to the CIA. (Monthly Review sheepishly notes that Sweezy was employed by the same office,[57] but fails to mention that Baran also worked for the Strategic Bombing Survey.) Adorno penned a piece for the CIA-funded outlet Der Monat, as if that somehow compromised his theories.[58] Rockhill dresses all this up in quasi-Marxist verbiage about the production, circulation, and consumption of knowledge, but his spiel really is this crude. Not that they are of comparable stature, but Lenin rode the sealed train car to Finland Station with German army officers.[59] Even Fidel Castro received CIA funds.[60]

Questions of selection, method, and framing in Losurdo’s interpretation

It was already mentioned earlier that Losurdo’s choice of figures to cover in a book entitled Western Marxism is unusual. Arendt and Agamben were never Marxists and, apart from a short flirtation with Maoism, neither was Foucault. One might argue with some justification that they have been important interlocutors for the Western left, such as it is, but it is disappointing that forty or so pages were devoted to these authors when Losurdo might have grappled with the circles around Socialisme ou Barbarie and Arguments, or even some of the Situationists. Castoriadis, Lefort, and Jean-François Lyotard during their Marxist years, or Lefebvre, Guy Debord, and Raoul Vaneigem at any point, would have been more appropriate objects for Losurdo’s analysis, given his remit. Jean Baudrillard’s early writings could have even made for interesting fodder. British Marxists like EP Thompson, Stuart Hall, and Raymond Williams might have easily fit into his survey. Meanwhile in the US, a whole universe of theorists could have been covered, starting with the Johnson-Forest tendency. Raya Dunayevskaya (Forest) and CLR James (Johnson), along with James and Grace Lee Boggs, all wrote important studies in the postwar period. Dunayevskaya had corresponded with Marcuse about philosophy.

Beyond this, as some reviewers have commented, the selection of texts dealt with in Western Marxism can be quite odd. One rightly remarked that “Losurdo’s procedure of building arguments out of a roving collage of passages taken from dissimilar documents seems to undermine many of his conclusions.”[61] Why spend so much time looking at the 1916 edition of Bloch’s Spirit of Utopia, or scattered statements by Lukács from 1915 and 1916? [62] Neither had yet become a convinced Marxist. For that same reason, does it really make sense to parse a lecture delivered by Horkheimer in 1970 or an interview conducted with Colletti in 1980?[63] Each of them had by then definitively turned away from Marxism. It is furthermore unclear from where Losurdo actually sourced a series of long blockquotes, attributed to Marcuse, that shows up in the second chapter.[64] The lines quoted there occur nowhere in the transcript of “The End of Utopia,” the talk he gave in the late sixties that is cited in the endnotes. Finally, Losurdo often neglected to engage with Western Marxists’ major theoretical works, preferring rather to dwell on minor occasional pieces. He did not tarry with della Volpe’s Logic as a Positive Science, for example, choosing instead to dwell on an obscure exchange with Norberto Bobbio over rights.[65]

Leaving aside such questionable decisions over what to include, one might ask how Losurdo treated the authors and texts he did select. Western Marxism moves via a series of jarring juxtapositions, setting passages from Adorno and Althusser side-by-side with quotations from Mao Zedong and Ho Chi Minh. Mention of Bloch’s early admiration of the United States is swiftly followed by: “Now let’s look at Ho Chi Minh.”[66] One of the German Marxist’s more mature treatises is immediately contrasted with a contemporaneous column by Mao: “Now, let’s look at the conclusion of the article by the Chinese Communist leader.”[67] Sometimes Losurdo simply placed a date next to a lengthy extract from Bobbio or Tronti and then went on to narrate some dramatic event going on around the time. “On May 7, 1954, at Dien Bien Phu, a popular army led by the Communist Party put an end to French colonial domination of Indochina.”[68] Meanwhile, Bobbio and della Volpe were wasting their time arguing whether or not the USSR enjoyed civil liberties. “We are in 1966.”[69] Just as Tronti published Workers and Capital in Italy, the Vietnamese were taking on the US military. Five years earlier, the US had launched an invasion of Cuba.

What these things had to do with each other is anyone’s guess. The point of all these non sequiturs, it turns out, is that Western Marxists had failed to follow the Hegelian injunction to comprehend their own time in thought. Hegel and Marx both had tall stacks of newspapers piled on their desks, proof that they were plugged in to current events.[70] By contrast, Marxist intellectuals across the West stayed aloof of the momentous struggles occurring in the world around them. If they had only paid attention, they might not have been so disconnected from the decolonization movements breaking out in the periphery. The revolution of the twentieth century (and perhaps even beyond) was not socialism versus capitalism, but anticolonialism versus colonialism.[71] Imperialism was the Hauptwiderspruch of the epoch. Overcoming capitalist social relations in pursuit of a communist future became of secondary importance.[72] National independence was the order of the day, since international revolution was off the table. Losurdo therefore preferred the social-patriotism of Ho and Mao to the rootless cosmopolitanism of Trotsky, Lukács, Benjamin, and Bloch, as a more fitting response to demands of the era.[73]

As the first name in this last list makes clear, Losurdo located the bifurcation between “the two Marxisms” inside the Bolshevik leadership group itself. “Trotsky, who saw the power achieved by the Bolsheviks as a trampoline to launch the revolution in the West, eminently represented Western Marxism,” wrote Losurdo. “Stalin was instead the incarnation of Eastern Marxism: He never left Russia, and… presented the proletarian revolution as a necessary instrument for reaffirming Russian national independence.”[74] Marx, Engels, and Lenin had all assumed that a revolution in the most advanced countries would be necessary to overthrow capitalism. It is true that they also had written—Marx and Engels occasionally, especially when it came to Poland and Ireland, and Lenin more systematically—in support of national liberation. But they did so mostly as an adjunct to world revolution, hoping to weaken reactionary strongholds like Russia and Britain,[75] or else destabilize the imperial core.[76] Losurdo, a self-styled realist, felt that classical Marxism’s assumption that revolution had to happen in the leading capitalist countries was unfounded and needed to be revised. Overcoming capitalism would be a much more drawn out process than Marx, Engels, or Lenin had imagined,[77] and would require state-building.

This brings in one of Losurdo’s favorite hobbyhorses: his thesis that the Marxist doctrine of the withering away of the state has had disastrous consequences for efforts to realize communism.[78] He made this argument again and again throughout his œuvre,[79] at times even arguing that the doctrine betrayed a harmful anarchist origin.[80] Whereas Marx, Engels, and Lenin had predicted the eventual disappearance of state power, Losurdo believed that this millenarian forecast stood in need of revision. As he put it, anticolonialism “was about liquidating colonial subjection to construct an independent national state.” Following 1917, “what inspired the revolution of subjugated peoples was not the password of ‘a state that is withering away’ but a state that is being built.”[81] In contrast to this more positive attitude toward the state, Western Marxists seized on the most utopian elements of Marxism, “accentuat[ing] the messianic tendency in Marx and Engels.”[82] Eastern Marxists were compelled to take the reins of power, and thus were not afraid to get their hands dirty.[83] Lenin purportedly moved away from the fantasy of the withering away of the state in practice, according to Losurdo, even if he never officially renounced it in theory.[84]

Both of these themes—the need for coordinated international proletarian revolution in the most advanced countries, and the reabsorption of state power by society—will be explicated further in the third part of this essay. Needless to say, Losurdo diverged sharply from what Marx, Engels, and Lenin had to say on each score. The next part of this essay, however, will look at the writings of the various Western Marxists he attacked in his book to determine whether the picture presented of them there lines up with what they actually wrote. His readings are so tendentious as to strain credulity, and must thus be compared with the source material to gauge the accuracy of his accusations. It will be shown that Losurdo almost habitually misrepresented the theorists he lambasted in Western Marxism, and that this belonged to a broader pattern of bad faith running across his works.

Thanks are due to Russell Jacoby for his helpful comments on the first part of this essay.

Nick Serpe, “Liberalism’s Exclusions and Expansions: A Review of Liberalism: A Counter-History,” Jacobin (№ 5: Winter 2012), p. 60. ↩︎

Fredric Jameson, blurb to the 2004 translation of Losurdo’s Hegel and the Freedom of Moderns. ↩︎

Angelo d’Orsi, “A Militant and a Scholar: Remembering Domenico Losurdo, 1941-2018,” translated by David Broder, Verso (29 June 2018). ↩︎

David Broder, “Eastern Light on Western Marxism: A Review of Il marxismo occidentale: Come nacque, come morì, come può rinascere,” New Left Review (Series II, № 107: October 2017), pp. 131-146. ↩︎

“Revisionism” can mean many things. Here it is meant in the specific sense of revising Marx’s revolutionary theory, as in the revisionist controversy of the 1890s between figures like Eduard Bernstein and Rosa Luxemburg. ↩︎

“The term ‘Western Marxism’ (and ‘European Marxism’) entered Marxist dictionaries in the early 1920s. The Soviet edition listed it as derogatory.” Russell Jacoby, Dialectic of Defeat: Contours of Western Marxism (New York, NY: Cambridge University Press, 1981), p. 59. ↩︎

Max Werner [Aleksandr Shifrin], „Der Sowjetmarxismus“, Die Gesellschaft: International Revue für Sozialismus und Politik (Volume IV, № 2: February 1927), pp. 42-67. ↩︎

l.h. [Karl Korsch], “The Marxist Ideology in Russia,” Living Marxism (Volume IV, № 2: March 1938), p. 50. ↩︎

“It is… completely against the spirit of the dialectic, and especially of the materialist dialectic, to counterpose the dialectical materialist ‘method’ to the substantive results achieved by applying it to philosophy and the sciences. This procedure has become very fashionable in Western Marxism.” Here Korsch should be read as implicitly criticizing Lukács. Karl Korsch, “The Present State of the Problem of ‘Marxism and Philosophy’: An Anti-Critique” [1930], translated by Fred Halliday, Marxism and Philosophy (New York, NY: Monthly Review Press, 2008), p. 134. ↩︎

Maurice Merleau-Ponty, “‘Western’ Marxism,” Adventures of the Dialectic [1955], translated by Joseph Bien (Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press, 1973), pp. 30-58. ↩︎

Grigory Zinoviev [Sinowjew], „Bericht über die Tätigkeit der Exekutive“ [19 Juni 1924], Fünfter Kongress der Kommunistischen Internationale, Band I (Berlin: Verlag Carl Hoym, 1925), p. 53. ↩︎

Maurice Merleau-Ponty, “Pravda,” Adventures of the Dialectic, pp. 59-73. ↩︎

Maurice Merleau-Ponty, “Sartre and Ultrabolshevism,” ibid., pp. 95-201. ↩︎

Very much as he would do in his preface to the 1967 rerelease of History and Class Consciousness, and much as Korsch had done in the thirties (albeit from the opposite angle). Kevin Anderson, Lenin, Hegel, and Western Marxism: A Critical Study [1995] (Boston, MA: Brill, 2002), pp. 298-300. ↩︎

Dick Howard and Karl E. Klare, The Unknown Dimension: European Marxism since Lenin (New York, NY: Basic Books, 1972). ↩︎

“Western Marxism as a whole paradoxically inverted the trajectory of Marx’s own development itself. Where the founder of historical materialism moved progressively from philosophy to politics and then economics, as the central terrain of his thought, the successors of the tradition that emerged after 1920 increasingly turned back from economics and politics to philosophy.” Perry Anderson, Considerations on Western Marxism (New York, NY: Verso Books, 1976), p. 52. ↩︎

“Born from the failure of proletarian revolutions in the advanced zones of European capitalism after the First World War, [Western Marxism] developed within an ever increasing scission between socialist theory and working-class practice… The result was a seclusion of theorists in universities, far from the life of the proletariat in their own countries, and a contraction of theory from economics and politics into philosophy. This specialization was accompanied by an increasing difficulty of language, whose technical barriers were a function of its distance from the masses.” Ibid., pp. 92-93. ↩︎

“The tradition descended from Trotsky has… been a polar contrast, in most essential respects, to that of Western Marxism. It concentrated on politics and economics, not philosophy.” Ibid., p. 100. ↩︎

See the chapter “Conformist Marxism” in Jacoby, Dialectic of Defeat, pp. 11-36. ↩︎

Ibid., pp. 108-109. ↩︎

See the chapter “The Marxism of Hegel and Engels” in ibid., pp. 37-58. ↩︎

“The predominance of philosophical works signified not a retreat but an advance to a reexamination of Marxism. Here I differ with Anderson’s deft Considerations on Western Marxism. I do not view Western Marxism as an unfortunate detour from ‘classical’ Marxism; nor do I look forward to its extinction.” Ibid., pp. 6-7. ↩︎

“This book takes its title from a 1976 book in which an English philosopher, Marxist, and communist (Trotskyist) militant invited ‘Western Marxism’ to finally declare its total distinctness and independence from the caricature of Marxism in the officially socialist and Marxist countries, all of which were in the East.” Domenico Losurdo, Western Marxism: How it was Born, How it Died, How it can be Reborn [2017], translated by Steven Colatrella and George de Stefano (New York, NY: Monthly Review Press, 2024), p. 37. Several reviewers have pointed out that Losurdo wrongly believed Anderson to have celebrated Western Marxism. E.g., Tom Canel, “Go East, Young Marxist?” Platypus Review (№ 172: December-January 2025). ↩︎

“[O]n the whole, Western Marxism missed the meeting with the world anticolonialist revolution.” Losurdo, Western Marxism, p. 140. ↩︎

“Addicted to the role of opposition and critique, and to varying degrees influenced by messianism, [Western Marxists] look with suspicion and disapproval at the power that [Eastern Marxists] are called upon to wield by the victory of the revolution.” Ibid., p. 200. ↩︎

“New Left Review could be taxed with having passed through phases of latent or incipient Third Worldism (1962-1963), Wilsonism (1964), Khrushchevism (1962-65), Guevarism (1967-1968), studentism (1968-1970), and Maoism (1968-1970). Overestimation of the peasantry and petty-bourgeoisie at the expense of the proletariat in the class bloc necessary to make the socialist revolution was combined with ingenuous illusions in Western social democracy, Soviet communism and Chinese communism as organizational forces working for world socialism, in different phases of the review’s evolution. The political record of New Left Review has in this respect been very checkered.” Anonymous, “Decennial Report” [1972], quoted in Gregory Elliott, Perry Anderson: The Merciless Laboratory of History (Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 1998), pp. 92-93. ↩︎

Anderson, Considerations on Western Marxism, p. viii. ↩︎

Duncan Thompson, Pessimism of the Intellect? A History of “New Left Review” (Monmouth: Merlin Press, 2007), p. 112. ↩︎

Anderson, Considerations on Western Marxism, p. 42. ↩︎

“Today, the full experience of the past fifty years of imperialism remains a central and unavoidable sum still to be reckoned up by the workers’ movement. Western Marxism has been an integral part of that history, and no new generation of revolutionary socialists in the imperialist countries can simply ignore or bypass it. To settle accounts with this tradition—both learning and breaking from it—is thus one of the preconditions of a local renewal of Marxist theory today.” Ibid., p. 94. ↩︎

Paul Piccone, “Twenty Years of Telos” [1988], Confronting the Crisis: Writings (New York, NY: Telos Press, 2008), p. 257. ↩︎

Paul Piccone, “Considerations on Western Marxism,” Telos (№ 30: 1976), pp. 213-216. ↩︎

Martin Jay, “Further Considerations on Anderson’s Considerations on Western Marxism,” Telos (№ 32: 1977), pp. 162-167. ↩︎

Andrew Arato and Paul Piccone, “Rethinking Western Marxism: Reply to Martin Jay,” Telos (№ 32: 1977), pp. 167-174. ↩︎

Jacoby, Dialectic of Defeat, p. 5. ↩︎

Paul M. Sweezy, “Paul Alexander Baran: A Personal Memoir,” Paul A. Baran, 1910-1964: A Collective Portrait (New York, NY: Monthly Review Press, 1965), pp. 32-33. ↩︎

Paul A. Baran, letter to Herbert Marcuse [7 October 1962], translated by Joseph Fracchia, The Baran-Marcuse Correspondence (1 March 2014). Accessed 16 March 2025. ↩︎

Citing Adorno’s “masterful” essay on Aldous Huxley in Paul A. Baran, The Political Economy of Growth [1957] (New York, NY: Penguin, 1976), p. 460. ↩︎

Paul M. Sweezy, The Theory of Capitalist Development: Principles of Marxian Political Economy [1942] (New York, NY: Monthly Review Press, 1970), pp. 11, 20-21, 31, 36; Paul M. Sweezy, The Present as History: Essays and Reviews on Capitalism and Socialism [1953] (New York, NY: Monthly Review Press, 1986), pp. i, vi. ↩︎

Paul A. Baran, letter to Paul M. Sweezy [5 December 1958], The Age of Monopoly Capital: Selected Correspondence, 1949-1964 (New York, NY: Monthly Review Press, 2017), pp. 224-225. ↩︎

Paul A. Baran and Paul M. Sweezy, “The Quality of Monopoly Capitalist Society: Culture and Communications” [1964], Monthly Review (Volume LXV, № 3-4: July-August 2013), p. 62. ↩︎

Richard D. Wolff, “Western Marxism,” Monthly Review (Volume XXX, № 5: September 1978), pp. 55-64; Joel Kovel, “Western Marxism” (Volume XXXIV, № 7: November 1982), pp. 56-63. ↩︎

John Bellamy Foster, “Western Marxism: A Dialogue with Gabriel Rockhill,” Monthly Review (Volume LXXVI, № 10: March 2025), p. 9. ↩︎

Ibid., p. 19. ↩︎

Gabriel Rockhill and Jennifer Ponce de León, “Socialism as Anticolonial Liberation: Contemporary Lessons from Losurdo” in Losurdo, Western Marxism, p. 15. ↩︎

Paul A. Baran, “On Soviet Themes” [1956], The Longer View: Essays Toward a Critique of Political Economy (New York, NY: Monthly Review Press, 1971), p. 372. ↩︎

Sweezy, “Paul Alexander Baran,” pp. 33-34. ↩︎

Paul A. Baran, letter to Herbert Marcuse [17 May 1954], The Baran-Marcuse Correspondence. ↩︎

Paul M. Sweezy and Leo Huberman, “The Split in the Socialist World,” Monthly Review (Volume XV, № 1: May 1963), pp. 1-20. ↩︎

“I don’t believe it is possible for a socialist society to develop a necessary civil society by capitalist methods, as Deng Xiaoping and his group apparently feel would happen if they continued the capitalist reforms which they initiated after Mao’s death.” Paul M. Sweezy, “Marxist Views: An Interview,” Monthly Review (Volume XLII, № 5: October 1990), p. 7. ↩︎

Unnamed, “Note from the Editors,” Monthly Review (Volume LXXIII, № 3: July-August 2021), pp. 155-156. ↩︎

Domenico Losurdo, “Has China Turned to Capitalism? Reflections on the Transition from Capitalism to Socialism,” International Critical Thought (Volume VII, № 1: March 2016), pp. 15-31. ↩︎

“[Imperialism] was… frequently ignored by the Western left… This went along with frequent attacks on the theories of dependency, unequal exchange, and world-system theory… One thinks of Robert Brenner’s attempt in New Left Review to designate Sweezy, André Gunder Frank, and Immanuel Wallerstein as ‘neo-Smithian Marxists.’” Foster, “Western Marxism,” p. 12. ↩︎

Anderson, Considerations, pp. 47-48. ↩︎

Paul Mattick, “Monopoly Capital” [1966], Anti-Bolshevik Communism (London: Merlin Press, 1978), pp. 187-209. Ernest Mandel, “The Labor Theory of Value and Monopoly Capital,” International Socialist Review (Volume XXVIII, № 4: July-August 1967), pp. 29-42. ↩︎

Franz Neumann, Herbert Marcuse, and Otto Kirchheimer, Secret Reports on Nazi Germany: The Frankfurt School Contribution to the War Effort [1942-1945] (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2013). ↩︎

Gabriel Rockhill and Zhao Dingqi, “Imperialist Propaganda and the Ideology of the Western Left Intelligentsia: From Anticommunism and Identity Politics to Democratic Illusions and Fascism,” Monthly Review (Volume LXXV, № 7: December 2023), p. 20. ↩︎

Gabriel Rockhill, “The CIA and the Frankfurt School’s Anticommunism,” Los Angeles Review of Books (27 June 2022). ↩︎

Lenin himself was probably not aware of the funds disbursed by the German government to the Bolsheviks, though he must have known Captain von Planetz and Lieutenant von Buhring were German military personnel. He knew everyone else in the train car personally. See documents 14-21, Germany and Revolution in Russia, 1915-1918: Documents from the Archives of the German Foreign Ministry, translated by Zbyněk Zeman (London: Oxford University Press: 1958), pp. 25-31. ↩︎

According to a journalist who was close with Castro, the CIA funded both sides of the Cuban civil war so as to muddy the waters. The total received by the rebels came to around $50,000. Tad Szulc, Fidel: A Critical Portrait [1987] (New York, NY: Perennial, 2002), pp. 427-428. ↩︎

Timothy Brennan, “‘Western Marxism’ is Not a Monolith,” Jacobin (4 November 2024). ↩︎

On the younger Bloch, see Losurdo, Western Marxism, pp. 44, 48-49, 53-54, 61, 63-64, 69-71. On the younger Lukács, see ibid., pp. 48, 61-62. ↩︎

On the older Horkheimer, see ibid., pp. 114-115, 143. On the older Colletti, see ibid., pp. 97-98, 224-225. ↩︎

Ibid., pp. 128-130. ↩︎

Ibid., pp. 95-96. He contrasted della Volpe’s response to Bobbio with that of Togliatti on ibid., pp. 92-95. Losurdo liked to cite this latter historic episode. See Domenico Losurdo, Democracy or Bonapartism: Two Centuries of War on Democracy [1993], translated by David Broder (New York, NY: Verso, 2024), pp. 250-251. ↩︎

Ibid., p. 71. ↩︎

Ibid., p. 111. ↩︎

Ibid., p. 94. ↩︎

Ibid., p. 99. ↩︎

Ibid., pp. 227-231. ↩︎

Losurdo’s second chapter is “Socialism versus Capitalism, or Anticolonialism versus Colonialism?” ↩︎

“[Imperialist aggression] made secondary the problem of building a socialist or communist society.” Ibid., p. 82. ↩︎

Ibid., pp. 48-53. ↩︎

Ibid., p. 68. ↩︎

“Just as [Marx] regarded the Polish question… as a lever for the overthrow of Russian dominance, so he regarded the Irish question as a lever for the overthrow of English world dominance.” Franz Mehring, Karl Marx: The Story of His Life [1918], translated by Edward Fitzgerald (Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press, 1962), p. 391. ↩︎

“The dialectics of history are such that small nations, powerless as an independent factor in the struggle against imperialism, play a part as one of the ferments, one of the bacilli, which help the real anti-imperialist force, the socialist proletariat [in big nations], to make its appearance on the scene.” Vladimir Lenin, “The Discussion on Self-Determination Summed Up” [July 1916], translated by Yuri Sdobnikov, Collected Works, Volume 22 (Moscow: Progress Publishers, 1964), p. 357. ↩︎

According to Losurdo, Mao had grasped this: “Far from being replaced or lost sight of, socialism became a goal spread over a much longer period than had been foreseen [by Marx, Engels, and Lenin]. On the other hand, it was also called for and pursued in the name of the conquest and defense of national independence.” Losurdo, Western Marxism, p. 87. ↩︎

“Often, Marxism has spoken of the disappearance of power as such—not the limitation of power, but its disappearance—the withering of the state and so on. This vision is a messianic vision, which has played a very negative role in the history of socialism and communism… [It] had terrible consequences in countries like the Soviet Union.” Domenico Losurdo, “Liberalism and Marx: An Interview with Pamela C. Nogales C. and Ross Wolfe,” Platypus Review (№ 46: May 2012), p. 3. ↩︎

“[T]he theory of the withering away of the state flows into an eschatological vision of a society without conflict that consequently needs no norms of legality to regulate or limit conflicts.” Domenico Losurdo, “Flight from History? The Communist Movement between Self-Criticism and Self-Contempt” [1999], translated by Charles Reitz, Nature, Society, and Thought (Volume XIV, № 4: October 2000), p. 505. ↩︎

“[Marx’s] extraordinarily insightful phenomenology of power ends up with a utopian and utopic ‘solution’ — the withering away of the state, a ‘solution’ that has played a catastrophic role in all attempts to build a postcapitalist or noncapitalist society… The fact is that, already in Marx, and even more so in the tradition that took its cue from him, one senses the negative influence of the anarchist tradition… This is the case even of Lenin’s State and Revolution.” Losurdo, Democracy or Bonapartism, pp. 320-321. ↩︎

Losurdo, Western Marxism, p. 49. ↩︎

Ibid., p. 39. ↩︎

“The bifurcation between Eastern Marxism and Western Marxism comes down to a contrast between Marxists who exercise power and Marxists who were in opposition and concentrated increasingly on ‘critical theory,’ ‘deconstruction,’ and denouncing power and power relations as such.” Ibid., p. 206. ↩︎

“[T]he challenges of leading a country strongly helped Lenin, Mao, and other leaders, and Eastern Marxism as a whole, to let go of messianic expectations and develop a more realistic vision of building a postcapitalist society.” Ibid., p. 206. ↩︎